Everything You Need to Know About the Election in 1968

The Ghosts of the '68 Election Nonetheless Haunt Our Politics

The "backlash" politics of criminal offense and race, an unpopular state of war, divided parties — sound familiar?

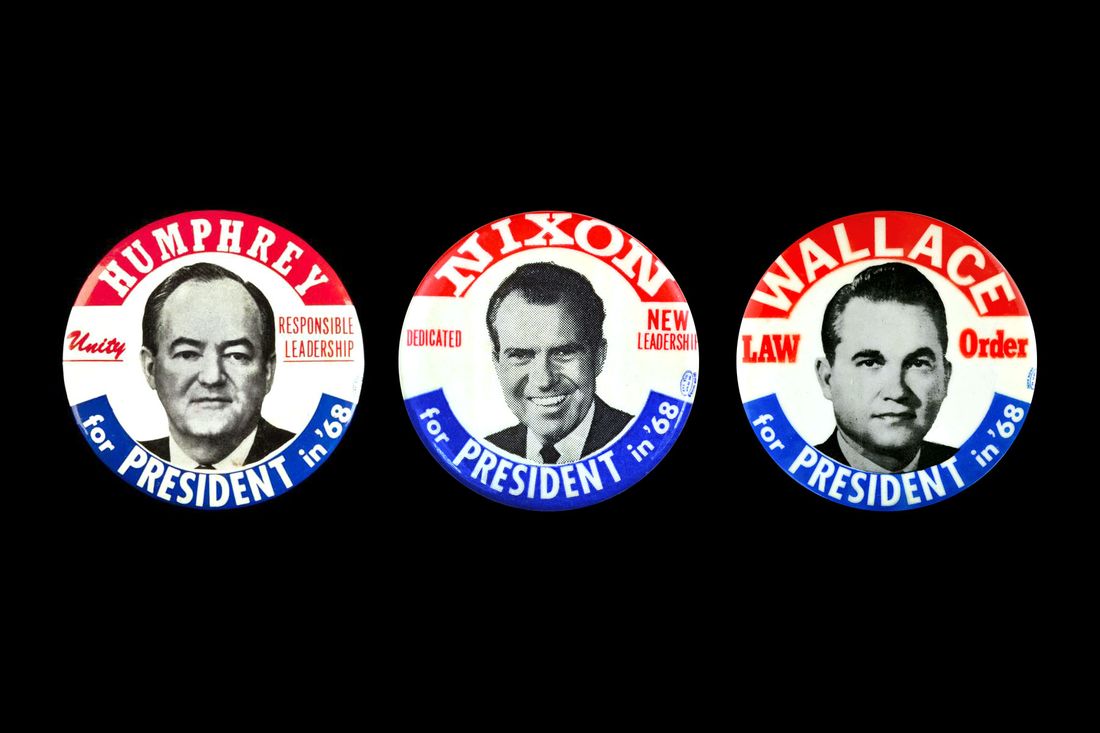

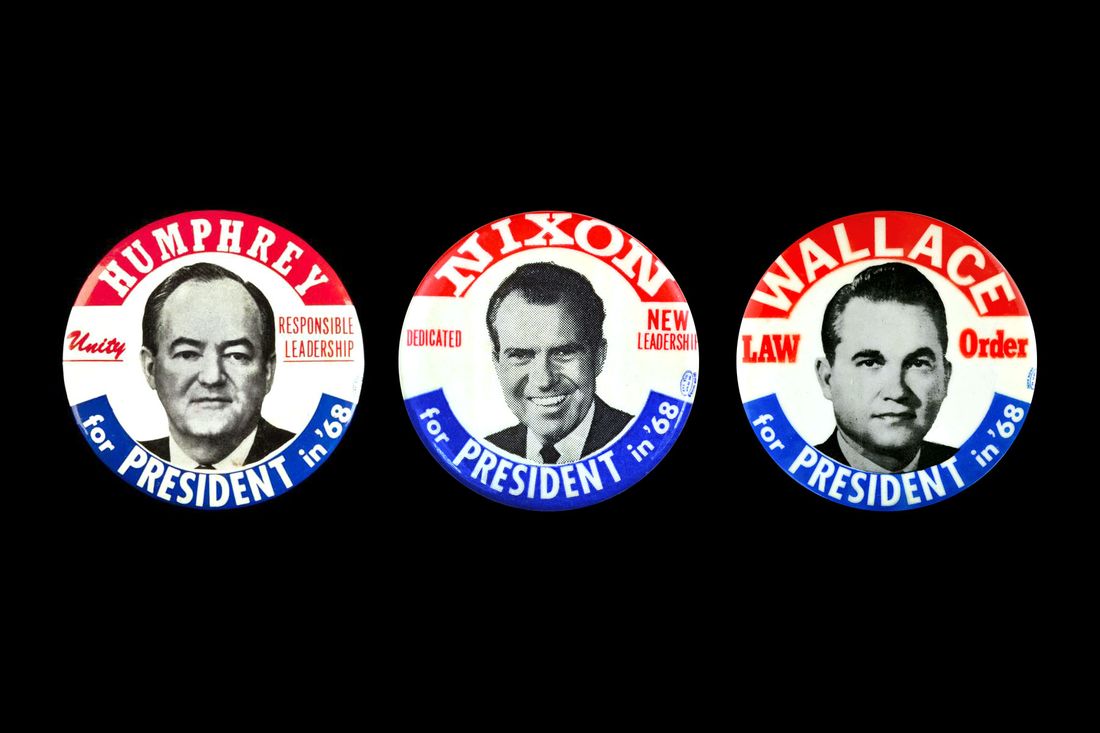

The Democratic, Republican, and American Independent candidates for president in 1968. Photo: Getty Images

The Democratic, Republican, and American Independent candidates for president in 1968. Photo: Getty Images

L years ago, Hubert H. Humphrey was in a globe of problem. The vice-president had been nominated as the Democratic candidate for president at a convention that was a political and public relations disaster. He was trailing badly in the polls. His political party was securely — possibly fatally — divided over the Vietnam War prosecuted by his chief patron, President Lyndon Johnson. And on summit of that, he was out of money.

A friend came forth to offering a helping hand (as the U.S. Naval War Higher's Richard Moss recalled concluding year):

In 1968, Moscow feared that the staunchly anti-communist Richard M. Nixon would exist elected. To preclude that, the Kremlin decided to reach out to Vice President and Democratic presidential candidate Hubert H. Humphrey. As Anatoly Dobrynin, the Soviet administrator to the United States from John F. Kennedy to Ronald Reagan, revealed in his memoir, "In Confidence," two decades ago: "The top Soviet leaders took an extraordinary step, unprecedented in the history of Soviet-American relations, by secretly offering Humphrey any believable help in his election campaign — including fiscal assist."

Dobrynin made the offering personally to Humphrey over lunch. He flatly rejected the idea. It's unclear who picked up the tab.

Nineteen-sixty-eight was an ballot year that featured a bit of everything, with a degree of volatility matching the times we are living through today. But it is mostly remembered for the events leading up to a riotous Democratic convention: 2 assassinations, a wave of deadly and destructive riots, intense presidential primaries, and the North Vietnamese/Viet Cong Tet Offensive that all only eliminated the possibility of an American military machine victory in Southeast Asia.

Less distinct in the Americans' collective retentiveness five decades afterward is the general election contest itself between Richard Nixon and Hubert Humphrey (with contained George Wallace lurking in the near background) — a race that, later on shaping upwardly every bit a complete blowout, became wild, dramatic, and very close in its final weeks. In retrospect, there'south no question that the '68 election helped remake American politics. It featured racial dynamics as powerful as those we witnessed 2 years ago; extreme partisan polarization; the original "Oct surprise," along with the aforementioned attempted intervention by the Russian government.

Nigh Americans who weren't of age in 1968 may recall we are today living through unprecedented trials and traumas. Merely the ballot of 1968 anticipated more of them than is oft recalled.

The final phase of the 1968 presidential contest resembled the Trump–Clinton battle in significant means. By the end of September, Richard Nixon had maintained a meaning lead for months. Though he'd had his own party unity problems in nailing downwards the GOP nomination, he faced an opponent with intense intra-party opposition, a funding disadvantage, perceived organizational incompetence, and a miasma of pessimism. Humphrey held little if any allegiance from antiwar Democrats later on the Chicago convention with its angry cops clubbing peace demonstrators and reporters akin. And he was losing millions of ancestral Democrats as well to the racist demagogue Wallace, whose southern base was bolstered by white working-class voters in many industrial states.

Antiwar voters were repelled by Johnson-Humphrey administration policies in Vietnam. Photo: David Fenton/Getty Images

A late September Gallup poll showed Humphrey with only 28 pct of the vote, only 7 percent more than than Wallace, 15 points less than Nixon — and not even half of the pct won past LBJ.

Simply, in the phrase of political historian Theodore White, "onetime political patterns that had seemed a few weeks agone to exist utterly torn, slowly, instinctively reasserted themselves" in the calendar month of Oct 1968. Since Democrats had built an enormous bulk only four years before (Johnson defeated Goldwater by a 61–39 popular vote margin, and carried 45 states, including some that rarely abandoned the GOP), the return to one-time partisan habits generally benefited Humphrey.

Still, it required a number of intersecting developments to modify the 1968 presidential election from a catastrophe for Democrats into a barnburner. The Humphrey campaign itself fabricated some important if overdue moves to restore political party unity. The Wallace campaign that had been eating away at Humphrey's spousal relationship base lost its fearful momentum. The Nixon campaign played it safe and tried to run out the clock. And objective events, particularly those involving the Vietnam War, played a role in tightening the election as well.

At the very nadir of his entrada, on September 30, Humphrey finally broke from the president, making a nationally televised oral communication in Salt Lake Urban center calling for a unilateral halt to U.S. bombing of N Vietnam, even though shadowy negotiations between his own administration and the Hanoi regime were under way. LBJ was not pleased. But instantly Humphrey's campaign started getting small-dollar campaign donations, and the antiwar demonstrators that had hounded his appearances on the stump vanished or even began cheering him.

More than importantly, the candidate and his campaign were transformed, every bit 1968 historian Michael Schumacher noted in his book The Contest:

"It liberated him internally," [Humphrey adviser] Ted Van Dyk told Albert Eisele, author of a dual biography of Humphrey and McCarthy. "The American voter watching the screen that night finally saw that Humphrey was for peace, that he was sincere, and that he meant information technology. On that night, the onus of the state of war shifted to Nixon."

"He was a new man from then on," Lawrence O'Brien alleged. "It was as if a burden had been lifted from his shoulders. And the touch on on the campaign itself was just as great."

Hubert Humphrey greets happy supporters after declaring independence from LBJ on Vietnam. Photo: Bettmann Archive/Getty Images

And as historian Michael Cohen observed in his book American Maelstrom, the voice communication was as well a turning bespeak for a Autonomous Political party that had frequently been as or more hawkish than Republicans in the fight against communism. Once marginalized, antiwar Democrats weren't just brought into the fold, they became the primary shapers of Democratic foreign policy:

For much of the previous year Democratic mandarins had sought to marginalize antiwar voices in the party by refusing to allow their views on Vietnam to shape policy or political decisions. By the fall of 1968 that position was no longer tenable. The antiwar faction had become too vocal, their advocacy too significant, and their influence in the party just also potent to be ignored…. From that point forward, they, not the hawks, would dictate the foreign policy direction of the Democratic Party. [Eugene] McCarthy had dealt the first accident, but in a very real sense, the Cold War bipartisan consensus died in Salt Lake Urban center on September thirty, 1968.

It was much similar the accommodation of Bernie Sanders supporters that the Hillary Clinton campaign executed in the 2016 full general ballot. It didn't win the election and so, either, but similar the loud-and-proud progressives that are playing so central a role in the 2018 midterms, the antiwar Democrats after 1968 were never outcasts once more, at to the lowest degree until September 11, 2001.

Former Alabama governor George Wallace entered the 1968 presidential campaign as the fiery embodiment of a backlash to the Democratic Political party'south decisive commitment to desegregation, reflected in LBJ's successful title of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and the Voting Rights Deed of 1965. In 1964 Wallace had proved that this backlash was not limited to the South by running in Autonomous presidential primaries in 3 states northward of the Bricklayer-Dixon line and winning larger-than-expected minorities of the vote. He chose the contained road in 1968, hoping to deny both major-party candidates an Electoral College bulk and giving himself and other southern reactionaries leverage over future civil rights efforts. And as the yr unfolded, Wallace showed more forcefulness in polls than any third-party candidate since the Progressive Party's Bob LaFollette in 1924.

Historians agree that multiple factors fed the steady pass up of Wallace's menacing presence that looked and so formidable up until the final month. At that place was increasingly negative media coverage of his campaign events, and the incitement to violence he regularly offered. In that location was the natural tendency of modest party candidates to lose altitude equally voters realized they couldn't win (Wallace'south actual strategy — denying Nixon and Humphrey an Balloter Higher bulk, giving the S a big bargaining chip for its regional grievances in an election to be adamant in the U.South. House — was also abstract and fanciful to energize bodily voters). And so in that location was an aggressive entrada past the labor movement — still very powerful 50 years agone — to convince their members that Wallace and his state were no friends of the working stiff.

Equally belatedly as September, polls of factories in the American heartland showed Wallace capturing good for you minorities and even pluralities of the union vote. Labor made minimizing Wallace's white working-class support the central feature of a massive push on Humphrey'south behalf, every bit it reminded voters in union households that Alabama was a state hostile to commonage bargaining with depression wages and terrible economic and social conditions for white equally well as black workers.

The Wallace campaign was no lucifer for labor's organizational muscle. But a final ingredient in Wallace's meltdown was an entirely self-inflicted wound that killed whatever momentum the peppery picayune demagogue took into October: the selection of legendary former Air Force Full general Curtis LeMay as Wallace's running mate on his American Independent Party ticket — and LeMay's complete self-destruction at the Oct 3 press conference that introduced him. Here's Schumacher'due south account in The Contest:

[LeMay] was in trouble from the onset, when he attempted to define his position on nuclear war. "We seem to have a phobia nearly nuclear weapons," he began, quickly adding that the all-time policy of all was to avoid war. Simply, he went on, if a country was going to appoint in state of war, the country had to exist dedicated to ending it every bit soon as possible.

"Use whatever strength that'south necessary. Possibly apply a trivial more to make sure it's enough to stop the fighting as before long as possible. So this means efficiency in the operation of the armed forces establishment. I remember in that location may be times when it would exist most efficient to utilise nuclear weapons. Nonetheless, the public opinion in this land and throughout the earth throw upward their easily in horror when you mention nuclear weapons, just because of the propaganda that's been fed to them."

It got worse, every bit a visibly dismayed Wallace fidgeted and occasionally tried to interrupt his freshly minted running mate:

The world, he insisted, wasn't going to end if nuclear weapons were deployed. He spoke of a motion-picture show he had seen, a documentary about the Bikini atoll, where many nuclear tests had been conducted. Life, he assured the astonished reporters, had returned to normal. "The fish are all back in the lagoons; the coconut copse are growing coconuts; the guava bushes accept fruit on them. As a matter of fact, everything is well-nigh the same except the state crabs. They get their minerals from the soil, I gauge, through their shells, and the land venereal were a little bit 'hot,' and in that location's a little question near whether you should consume a land crab or not."

[T]hus, in the span of a cursory press conference, Curtis LeMay nuked George Wallace's campaign.

The disastrous press conference where George Wallace introduced Curtis Lemay every bit his running mate.

While Wallace dropped from 21 percent in that late-September Gallup poll to xiii.v percent in the final results, and failed to knock the election into the House, he did take a major outcome on the campaign. He was enough of a threat to Nixon in the southern edge states that the Republican began echoing his racist dog whistles, often through the "law-and-lodge" stylings of his own running mate, Spiro Agnew, who earned a spot on the ticket via some tough rhetoric aimed at African-American protesters in Maryland. The GOP also deployed right-wing southern Republicans like 1948 Dixiecrat presidential candidate Strom Thurmond to undercut Wallace. In fact, the "Southern Strategy" that characterized Nixon's 1972 reelection campaign and the GOP's national efforts in later years began as a flanking maneuver against George Wallace.

Despite its occasional abrupt edges, Nixon's campaign was a model of studied vagueness designed to maintain his once-substantial lead. In the Southward he was the candidate of racial conservatives who "preferred a more conventional church building-usher respectability in their spokesman," every bit Wallace biographer Marshall Frady put it. He also exploited his shut friendship with the Reverend Baton Graham to entreatment to white Evangelical voters in the Due south and elsewhere. Some Democrats and fifty-fifty more independents who were hostile to the Johnson-Humphrey administration'southward Vietnam policies were able to squint at the old Cold Warrior and perceive a peace candidate (Nixon consistently claimed that taking a specific position on Vietnam during the campaign would undermine Johnson'southward stewardship of the war and/or his peace negotiations). He played to the political center equally Wallace raged on the right and Humphrey tried to energize the left.

Only Nixon lost much of his lead down the stretch (Gallup showed his lead shrinking from 15 points in late September to 8 points in late Oct then merely one point on election eve).

The Johnson assistants had been engaged in preliminary negotiations with North Vietnam since April, with Hanoi insisting on an unconditional bombing halt among other concessions, and Washington requiring a sign-off from the South Vietnamese government. Of a sudden, in the fall, the Soviet Spousal relationship (a major supplier for Hanoi) began pushing both parties toward more serious negotiations. And by tardily Oct the Johnson administration had worked out a circuitous formula where the U.Due south. would declare a bombing halt with the understanding that Hanoi would not exploit the situation by ratcheting upwardly attacks on Southward Vietnamese cities. On October 31 LBJ went on national television and appear a cessation of all bombing of North Vietnam.

This announcement, which was intended at least in part to give Humphrey a heave, was rapidly torpedoed when the South Vietnamese government made it known it would non participate in the fresh negotiations the bombing halt had produced. And in that location'due south no question that the Nixon campaign, operating through an old China Lobby leader and close Nixon associate, Anna Chennault, strongly encouraged Saigon to exercise merely that. Equally Perlstein recounts, Chenault told the South Vietnamese that sabotaging Johnson's initiative would throw the election to Nixon, who would offer them better terms in an eventual peace understanding.

Johnson was on to Nixon's gambit, which he called "treason" in a phone conversation with Republican Senate Leader Everett Dirksen. Just he chose non to publicly betrayal it before the ballot (in function because the reason his administration knew nearly it in the first place was because information technology was illegally surveilling Chennault). Given Nixon's pious refusals to talk almost Vietnam out of concern for interfering with the Johnson assistants's war and diplomacy, his entrada's cloak-and-dagger scuttling of a peace initiative was infamously ironic.

In a conversation with Republican leader Everett Dirksen, LBJ accuses Nixon entrada of "treason."

So in effect Johnson tried to pull an October Surprise and Nixon countered with his own. The election took place under a confusing deject of dashed prospects for peace in Vietnam, though the public didn't find out well-nigh the strange Spy vs. Spy machinations involving the 36th and 37th presidents until much later.

According to Theodore White, pollsters were picking up a trend toward Humphrey amid women, owing, they thought, to the terminal-minute talk of a Autonomous-negotiated peace in Vietnam. So the Nixon campaign deployed a 30-minute biographical advert that emphasized his sunnier characteristics — particularly the formative influence of his Quaker female parent, Hannah:

All day Monday and Tuesday, on any time they could purchase regionally or nationally, they ran their Nixon half-hour biography, starting in Whittier, lamentable, sweet, nostalgic, full of sentiment and mother love to achieve the hearts of American women whom they might catch between dish-drying, housecleaning, and the pick-upwards of children from school. They spread Nixon's message more finer than did Humphrey's mediamasters, who made a poorer showing of the biography of their champion. The Humphrey biographies, curiously, fabricated Humphrey seem a man thrust forward only by issues; the Nixon biographies made Nixon seem a man of center.

Both campaigns also utilized that great lost art form of 20th-century political theater, the Ballot Eve telethon, where candidates (and commonly celebrities) made their concluding pitches in an extended format that included call-ins, entertainment and lots of rah-rah cheerleading. Schumacher assessed the Humphrey and Nixon telethons:

The next day, the final one before the ballot, the two candidates jousted in split Los Angeles goggle box studios in nationally broadcast telethons, Humphrey on ABC, Nixon on CBS. Humphrey, with Ed Muskie at his side and former McCarthyites Paul Newman and Joanne Woodward taking calls in the background, turned in a offset-rate performance. He and Muskie took questions phoned in from beyond the U.s.a.. By his own assessment, Humphrey still felt energized from his previous day's appearance at the Astrodome, and information technology was evident in the old, talkative Humphrey prototype projected on television screens from coast to declension. His questions, covering the gamut of issues raised throughout the campaign, were not screened, and Humphrey and Muskie worked like a tag team in answering them. Eugene McCarthy called unexpectedly and offered his all-time wishes, saying that he hoped his support would be helpful …

At that place was too a taped Ted Kennedy tribute to Humphrey, lending a chip of the Camelot magic to the political leader whom John F. Kennedy had routed in the 1960 primaries.

The Nixon telethon was a more somber outcome:

The scene at his television receiver studio contrasted the vivacity of the Humphrey set: Nixon, sitting stiffly in a chair and looking tired, spoke in a calm, authoritative vocalism, but in that location was little life to him. He would be in control until the biting finish. Bud Wilkinson, the revered football game double-decker and a strong public supporter of Nixon throughout the entrada, acted as the telethon's host. He carefully screened calls from viewers, asking Nixon the nigh full general, easiest to respond questions; there would be no slipups on the last mean solar day. The cherry-picked studio audience reacted to Nixon equally expected. The telethon resembled Nixon'south commercial tapings in New Hampshire eight months earlier: in a controlled atmosphere Nixon looked downright presidential….

Spiro Agnew, the ane human who could have inflicted damage in the telethon, was nowhere to be seen.

Jackie Gleason supplies a small dose of celebrity appeal at Nixon's preelection telethon.

So the two campaigns ended as they began, one in energetic disarray, the other in tedious and manipulative self-control. And an estimated 48 million people watched the telethons; the side by side twenty-four hours, 73 meg would vote.

The final polls pointed to a dead rut, with Gallup showing Nixon hanging onto a i-point (43/42) lead and Harris showing Humphrey finally pulling into the lead (43/40).

Gallup was close to predicting the results exactly: Nixon won 43.4 pct of the popular vote while Humphrey won 42.7 pct (Wallace finished with thirteen.5 percent). Information technology was the fifth-closest presidential election every bit ranked by percentage of the popular vote. Nixon's 110-vote Electoral College margin (301–191) was more comfortable, but he was but 31 to a higher place the bare majority necessary to win (Wallace had 46 electoral votes from the five southern states he carried). As Michael Cohen noted in American Maelstrom, a shift of 42,000 votes in three states (Alaska, Missouri and New Jersey) from Nixon to Humphrey would take thrown the election into the Business firm with its Democratic majority.

While at the fourth dimension Humphrey'southward comeback and nigh-win got the about attention, the baleful refuse in Democratic fortunes later on LBJ's 1964 landslide was near significant in hindsight. As Cohen observed:

Forty percent of Johnson voters in 1964 bandage a ballot for Nixon in 1968. In all, 57 percent of the American electorate voted against the Democrats and chose a conservative or middle-right candidate. Not since Hoover's loss in 1932 had an American political party seen such a four-year reversal of fortune.

Information technology became abundantly clear to Republicans (notably young Nixon adjutant Kevin Phillips in an analysis that turned into his influential 1969 book The Emerging Republican Bulk) that consolidating the Nixon and Wallace votes could give the GOP a sizable advantage, which is precisely what Nixon did in 1972.

Nixon'southward narrowly successful 1968 campaign quickly led to his landslide reelection — and and then his scandal-forced resignation. Photo: Dirck Halstead/Getty Images

The Nixon assistants certainly tried to feed this transformation via continued rhetoric aimed at antiwar liberal elites ("an effete corps of impudent snobs," in the words of Nixon'southward assail-dog vice-president) and demands for police force-and-order legislation and Supreme Courtroom decisions. But the president's paranoid personality quickly began to shape his politics in means that somewhen led to his downfall, as Rick Perlstein observes in Nixonland:

Every morning, staffers would written report [communications director] Herb Klein's face to know how to handle the dominate that day….Hours were taken upward after important meetings grilling [principal of staff Bob] Haldeman or his national security advisor, Henry Kissinger, about whether he did well or bragging virtually how well he did….

Nixon would prevarication about annihilation: spreading give-and-take that he took no naps even though he took them almost daily; challenge to the Quango on Urban Affairs that his management philosophy was to stick to the big picture… even though precious hours of the Leader of the Free Earth'southward time were spent worrying over details such as the spray of the presidential shower, or the precise lighting angles in his idiot box appearances.

At least Nixon didn't take Twitter.

When the Watergate scandal (or more accurately, his endlessly mendacious and cocky-destructive handling of the scandal) eventually brought Nixon downward, the young liberal antiwar politicians of the Autonomous Political party had a brief ascendancy after a sensational midterm election in 1974, and Republicans were temporarily chastened and moderated under the leadership of appointed vice-president so president Gerald Ford. It helped that Spiro Agnew, that smashing champion of what would later be called "culture war" politics, had been forced to resign after being caught in a petty bribery scheme that dated back to his days every bit Baltimore County Executive. But Ford near lost the GOP nomination in 1976 to Ronald Reagan, one of Nixon's nigh resolute defenders. And miraculously, in 1976, Democrats won back the Wallace vote.

Jimmy Carter ran a southern pride–suffused candidacy that was actually endorsed past George Wallace post-obit his near-assassination and the failure of his ain Democratic nomination entrada. Carter won eleven of the 13 states (all but Oklahoma and Virginia) in which Wallace had taken more than 18 percent of the vote in 1968. The regional effect subsided in 1980, although Carter still performed well above his national percentages in united states of america carried by Wallace in 1968. There were even pocket-sized echoes of this regional Democratic improvement in the Clinton-Gore campaigns of 1992 and 1996 (which helped create a popular theory that just southerners could win the presidency on the Democratic ticket).

But overall, the unquestionably dominant upshot of the 1968 presidential election was to advance an ideological sorting-out of the two major parties. Henceforth Democrats became gradually more dependent on minority and cocky-consciously progressive voters while Republicans expanded their former farm-and-land-order coalition by exploiting the racial and cultural fears of white working-class voters. Nixon'southward 1972 landslide majority led to Reagan'due south 1984 landslide majority. Republicans built on Nixon'due south relationship with Baton Graham to aid develop a Christian right movement closely aligned with the GOP. And at present the partisan and ideological lines kickoff seen clearly in 1968 have hardened despite — or perhaps because of — major demographic changes that take diversified the nation and threatened white male hegemony.

Donald Trump'due south 2016 campaign was to a remarkable extent an amalgam of the Nixon and Wallace approaches in 1968. Nixon talked nearly a "silent majority" and "forgotten Americans" in his 1968 acceptance spoken communication at the Republican National Convention. Trump used the "forgotten men and women" terminology in his election nighttime victory speech and his inaugural address. Both were pretty obviously referring to "constabulary-abiding middle-form folk" tired of "demanding minorities" and youthful disorder. Trump'due south constant attacks on "elites" are less-coherent echoes of Spiro Agnew'due south rhetoric. Trump's insecurities and hatred of the media are Nixonian to a tee.

But George Wallace's campaign provides the most hit forerunner of Trump '16 in its sheer crudity and thinly suppressed violence. Trump's famous rallies, which accept continued into his presidency, may not take been modeled on Wallace's a half-century agone, but there are definite similarities, as this business relationship of an event at Madison Square Garden from Michael Cohen'due south American Maelstrom illustrates:

Exterior the arena shoving matches and fistfights broke out repeatedly equally Birchers, Nazis, and Klansmen tussled with Trotskyists, Yippies, and Black Power activists … Rocks and soda bottles, from both sides, pelted the cops, who were trying, without much success, to keep order …

With the crowd inside at a fever pitch, the guest of honor arrived under the watchful eye of hundreds of police officers. George Wallace was greeted with a sound so overwhelming that even the jaded political reporters who had seen and heard information technology all were momentarily stunned. "It was uncontrolled release of frenzied, pulsating passion that seemed almost more sexual than political … Information technology may have been the loudest, most terrifying sustained human din ever heard in New York," wrote Robert Mayer in Newsday. "Wallace at MSG was the dark-side equivalent of the Beatles playing Shea Stadium …"

Then, with the traditional ambulation of grievances, the sermon began. Wallace fired broadsides against the "pseudo-intellectuals" and "theoreticians," the "anarchists," "the liberals and left wingers," the "he" who looks like a "she," and the professors and newspapers that "looked down their nose … at the boilerplate man on the street." His pledges to "let the police handle" the country'southward rising criminal offence issues.

George Wallace at 1 of his wild rallies.

Like Trump, Wallace baited the media, pointing them out to his fans for aroused derision. And like Trump, Wallace seemed to feed on the fury of his audience, leading him to feed it with ever-more passionate expressions of resentment. Wallace even anticipated Trump on policy matters — non merely his heavy-handed approach to offense, but his Jacksonian hatred of "no-win wars" (his basic posture on Vietnam), and the distinctions he was willing to describe betwixt government benefits for virtuous white middle-grade folks and those for welfare freeloaders. This description of Wallace voters should be familiar to observers of Trump's base of operations:

[Wallace voters] were far more likely to exist supportive of government spending than traditional conservative voters. They only preferred the kind of spending that benefited them. When the American Independent Political party issued its platform in October 1968, it called for greater government engagement in about every other facet of American life: more job grooming for "all Americans willing and able to seek and concur gainful employment; more federal monies for transportation, instruction, and even the space program; a significant increase in Social Security benefits; and more support for elderly health care."

Trump, of course, conquered one of the two great American major parties, so in some respects he represents Wallace'due south ultimate triumph over Nixon'south GOP.

It's too early to discern whether Trump, like Nixon, will come to grief thanks to his ain and his associates' corruption, hubris, and paranoid myopia; he'southward certainly far down the Nixonian path, as the constant Watergate analogies (such as the "Sat Night Massacre" a firing of Jeff Sessions or Rod Rosenstein would be described) he inspires would indicate. But while Nixon did anticipate a largely successful (if often immoral) political strategy that others deployed successfully, it's unclear whether his legacy will include anything valuable salvaged from the angry rhetoric and the thinly veiled white nationalism. Fifty years after the 1968 presidential election, the same conflicts over race and grade, crime and punishment, war and peace, interests and identity, rage on.

Source: https://nymag.com/intelligencer/2018/10/1968-election-won-by-nixon-still-haunts-our-politics.html

0 Response to "Everything You Need to Know About the Election in 1968"

Post a Comment